Flatiron's Guide to Cote Rotie

Allen Meadows, more familiarly known as Burghound, was once asked what wines he likes to drink most from outside of Burgundy. His answer was Cote Rotie. I've heard this kind of answer again and again from wine drinkers who love Burgundy.

No other region can produce wines that are closer to Burgundy in terms of weight, texture and elegance. If you like Burgundy, you almost certainly like Cote Rotie ("Côte-Rôtie" in proper French; I'll stick to the simpler un-accented/un-hyphenated English version in this guide).

If you want just one way of explaining this Burgundy affinity – and of understanding Cote Rotie more generally – it is this: Cotie Rotie is the Northern Rhone in extremis. Take everything you know about the Northern Rhone, exaggerate it a little bit, and you end up with Cote Rotie. This will be a constant theme as we go about unpacking the AOC for you.

Geography: Cote Rotie is in the North of the Northern Rhone

(E. Guigal map of Cote Rotie)

Yes, the Rhone does not get more Northern than Cote Rotie! It is at the very top, the northern end of the “string” that I describe in my overview of the Northern Rhone.

In fact, it is so far north, that it is remarkably close to Beaujolais! I can’t think of a better way to convey this than this clever map that I recently found during my research: a subway map of France’s wine regions. As you can see, Cotie Rotie is just one stop away from Beaujolais, which is technically part of Burgundy. Another way to think about it is this: Ampuis, the principal village of Cote Rotie, is as close to Meursault as it is to Chateauneuf-du-Pape.

This is all reflected in the wine itself. Even more than the other wines of the Northern Rhone, Cote Rotie acts and tastes like a wine of the North. It is tense and acidic. It translates terroir more than fruit.

Grape Varieties: Syrah Of Course, but with a Twist

Although the Northern Rhone grows only Syrah for red wine, it is occasionally blended with white grapes. This is permitted pretty much throughout the Northern Rhone, including St. Joseph and Hermitage. But they almost never actually add white grapes to those wines.

Cote Rotie is different. Here, up to 20% of Viognier may be added to Cote Rotie. Unlike in Hermitage and St. Joseph, in Cote Rotie this red-white blending is relatively commonplace.

And it makes a big difference! Further south, in Hermitage and St. Joseph, the white grapes are Marsanne and Rousanne. Neither grape has the aromatic intensity – very floral, very fruity – of Viognier. Viognier is part of the explanation of why Cote Rotie is lighter in weight, and more “Northern” in personality.

Climate

Temperature

But the main reason that Cote Rotie is more “Northern” in personality, is because it is cooler. The average annual temperature in Cote Rotie is around 11.9 degrees Celsius. That’s closer to the average temperature of Beaune, in the heart of Burgundy’s Cote d’Or, where the average temperature is 10.8 degrees, than it is to Avignon, the heart of the Southern Rhone, where the average temperature is 13.7 degrees. When it comes to climate, Cote Rotie is definitely more northern than southern.

Slopes and Winds

Cool temperatures means we are at the margin of where Syrah can ripen. You need every ounce of warmth you can muster to get the grapes to that perfect point of balance where you have ripe fruit that remains in tension with its acidity and tannin.

In Cote Rotie, they achieve this through very steep – up to 60 degrees steep! -- slopes that face the sun. Cote Rotie -- "Côte-Rôtie" -- is French for “roasted slope”, and that is a reference to those sun-soaked south-facing slopes. In fact, the slope is running roughly northeast to southwest, very close what you find in Grand Cru Burgundies, for example. In Burgundy, the lean is a little more towards east, and in Cote Rotie, a little more towards south -- Syrah needs more sun!

Temperature is also affected by the winds. The Northern Rhone is frequently afflicted by the bise, a cooling wind that blows in from the north. By locating on hillsides that face south, these cooling winds are blocked, and the grapes can ripen....just.

History: The Story of the Northern Rhone, but on Steroids.

Wine history can be boring, but there is one thing you need to know about Cote Rotie: its story is an extreme version of the Northern Rhone’s.

Cote Rotie Almost Disappears

The Northern Rhone, as I wrote in my overview, went into a period of substantial decline after the ravages of phylloxera, two World Wars and the Great Depression. Cote Rotie almost disappeared entirely.

In the late 1940s, the AOC of Cote Rotie was practically worthless. Few producers even bothered to put its name on a label. Even though the AOC had already been introduced, most people continued to sell their wine as cheap Vin de Table. So cheap, in fact, that most farmers stopped producing wine and switched to crops like apricots, which yielded five times as much revenue for the same amount of land.

It didn’t help that Cote Rotie is practically a suburb of Lyon and there were always new things to build. Why grow worthless grapes when you can just sell your land to a developer with visions of a new gas station?

I have not seen precise estimates of how small Cote Rotie became during this period, but it could have been as little as 50 hectares of wine production -- the size of a single mid-size Chateau in Bordeaux.

Cote Rotie Roars Back to Life

Today, Cote Rotie is roughly five times that size. It is two and a half times the size of Hermitage, or roughly the size of Chambolle Musigny and Vosne Romanee combined.

As it has grown in size, so it has grown in price. New releases of the very top Cote Roties – from Guigal – cost as much as top Hermitage, several hundred dollars a bottle. At the bottom end, the cheapest bottles in the U.S. can be found for around $50, just a little below the starting point for Hermitage. A lot of great Cote Rotie can be purchased today for about $70 or $80 – a pretty good value, I think, compared to equally-priced Burgundies.

Gentaz!

But it’s impossible to tell this story without referring to Gentaz-Dervieux. Gentaz made a small amount of Cote Rotie in a fastidiously traditional manner (he was rumored to age his wine in some barrels that were a century old!) up until his retirement in 1993. He sold them for very modest prices, and I have friends who purchased them in the 1990s from his importer, Kermit Lynch, for under $50 per bottle.

Today, those bottles are worth $2,000 each or more. Partly, this has to do with the diminishing supply of available bottles – he stopped making wine in 1993, and there can’t be many left! But tiny supply only results in stratospheric prices when the demand is there.

And it’s on the demand side that the Gentaz story is so interesting. For years, Robert Parker and other critics were telling us that bigger, riper, plusher, oakier wines were better. They got better scores. This helped drive up the prices of Guigal’s Cote Roties, which very much came to be made in this style. (And how could I get so far in this history of Cote Rotie barely mentioning Etienne Guigal? That guy, with his commitment to quality and his excellent marketing skills, played a huge role in Cote Rotie’s post-war recovery.)

But anyway, Gentaz’s wines weren’t at all like Guigal’s. They were traditional. Lighter. More "northern". Not oaky at all. Old fashioned. At some point in the 2000s, it started to dawn on people that this is how they liked their Cote Rotie. And they wanted to drink Gentaz’s wines really badly.

This, I think, is the whole key to understanding why Cote Rotie has become so successful. American taste, and maybe even global taste, has veered away from the “Parker palate” to a taste for elegance. Cote Rotie, situated in the perfect place to produce elegant Syrah, has reaped the benefits.

A Golden Age

So Gentaz takes us into Cote Rotie’s golden age – too golden for many pocket books, you might think. Fortunately, you don’t have to fork over $2,000 for admission. Plenty of producers are making wines today that echo the magic that Gentaz was able to conjure. I will profile some favorites a bit later.

Soils: Granite, of course, but What Else?

In your first lesson on Cote Rotie, you usually hear that it is all about Cote Brune and Cote Blonde. These terms are sometimes used loosely to refer to entire slopes, each consisting of many different vineyards. But look at a vineyard map of Cote Rotie, and you’ll see that they are actually the names of specific sites, and that these sites comprise only a tiny amount of vineyard land in the middle of the AOC.

But the two sites – aside from being among the very best -- do stand at a crucial dividing point. Master this, and you unlock the key to understanding Cote Rotie’s soils.

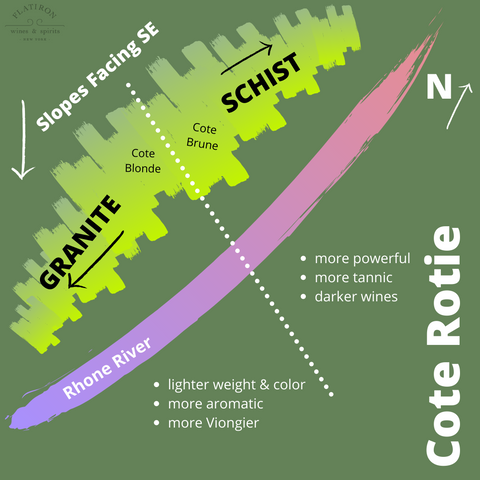

Essentially, the Cote Brune, and everything north of it, consist of schist-based soils. The Cote Blonde, and everything south of it, are based on granite.

The schist soils give you more powerful, tannic, darker wines.

The granite soils give you lighter wines – both in weight and in color – that are more aromatic.

Here is a one way to think about it. Condrieu, where they make 100% white wines from Viognier, is located just to the south of Cote Rotie. The AOC police necessarily had to put a hard border between Condrieu and Cote Rotie, but the laws of nature -- and terroir -- follows a continuum. So the further south you go in Cote Rotie, the more likely you are to find terroir suitable to Viognier. Indeed, almost all the Viognier in Cote Rotie is grown in the southern, Cote Blonde, half of the AOC. So the further south you go, the more the terroir is suitable to lighter, more aromatic wines -- until you cross the legal boundary and suddenly such wines are mandated.

There are details of course – varying amounts of mica, feldspar, gravel, and so on – but master the schist/granite distinction and you will get through just about any conversation on the subject.

Top Sites

Like Burgundy, and most other French wine regions, the Cote Rotie can be divided into villages. By far the most important of them is….

Ampuis -- Ampuis is in the middle of Cote Rotie. It is the AOC’s biggest and most important town. (Though it really isn’t very big.)

It is also home to Cote Rotie’s oldest, most historic vineyard sites AND it is the village through which the tributary Reynard runs and flows into the Rhone. The Reynard is significant because it is the geologic divide between the schist soils of the northern half of the AOC, and the granite soils of the south. It's a good name for a restaurant!

Cote Brune – This, of course, is the greatest vineyard in the northern, “Cote Brune” side of the AOC. Yes, it has plenty of schist, as well as iron and manganese in the soils (you also find manganese in Moulin-a-Vent in Beaujolais and Brunate in Barolo ; it enhances the wine’s structure). Those supplements help give the soil a brown color, and hence its name.

Unlike most of the AOC, the Cote Brune faces due south. It gets lots of sunshine, and therefore produces ripe grapes to balance out the intense tannins. The wines it produces are marvelous. Gentaz’s wines were from here (his vines are now worked by Rostaing). Jamet has a plot here, where he makes what could be the greatest Cote Rotie of today. Guigal’s La Turque is also in the Cote Brune.

Cote Blonde – On the other side of Reynard is the almost equally esteemed Cote Blonde. Right away, it is clear that you are on the other side of a great geologic divide. You have granite! You have Viognier! Therefore, the tannins are softer, the fruits redder, and the floral notes pronounced.

Like the Cote Brune, portions of this site face south – there is a reason that this is the historic core of Cote Rotie, and it is that these were the sites where it is easiest to ripen grapes! – but a portion also faces southeast. Many of the AOC’s most recognized names have vineyards here, including Rostaing and Barge. Guigal’s La Mouline comes from here.

Chavaroche – Not the most famous site, but important to us, because Bernard Levet produces a single vineyard Cote Rotie from here (more on the producer below). It borders Cote Brune (near its top) and shares the brown color. But here the schist is more pure, and the slopes start to tilt southwest. These little things matter. It produces very fine but sturdy wines – Levet's importer Neil Rosenthal calls the wine produced here “ferocious”.

La Landonne – Go upstream from Cote Brune and you soon get to La Landonne, just where there is a slight curve in the river. As a result of this curve, you start to get into vines that really point the classic southeast: south means sunshine, east means the gentle morning sun.

Your soils here are rich in schist and iron ore, and you get wines that almost exaggerate what you’d expect from the schist side of Cote Rotie’s divide: dark-fruited, brooding wines. Besides Guigal’s La Landonne, you find a great single vineyard from Rostaing, as well as vines that serve Jamet and Xavier Gerard.

Cote Rozier – Cote Rozier, and its extension above, Rozier (yeah, same name but without the "Cote" -- just as confusing as the "Brouilly -- Cote de Brouilly" situation in Beaujolais), form the last vineyards in Ampuis before you get to the village of Verenay. We are now most definitely facing southeast – and I really mean “face” in the vertical sense of the word, as here you find some of the steepest sites in all Cote Rotie.

You still have classic schist Syrah, with loads of tannins, but not quite the same degree of finesse as you get just slightly to the south. Still, you get some first division wine here, including Ogier’s Belle Helene, and also grapes that are used by Jamet, Guigal, Bonnefond and Gangloff.

Verenay - Verenay is the next village upstream from Ampuis, though its small collection of buildings sits not directly on the Rhone but on the other side of the N86, the auto route that runs between the river and the vine-covered slopes, and then cuts through the middle of Ampuis. The vineyards above Verenay produce big, long-lived Cote Roties.

Grandes Places – Grandes Places is Verenay’s top site. It is rocky and windy and southeast facing. It has bits that are flat and bits that are very steep. As you would expect north of the Cote Brune, there is plenty of schist in the soils. This site produces long-lived, powerful wines that are not without finesse and fine tannins. Clusel Roch makes a 100% Grandes Places that is quite exceptional.

Vialliere – This is a name you see a fair bit, as the site is about 10 hectares and lots of bottles bear its name. It neighbors Grandes Places and its terroir is similar, though Vialliere is particularly steep. The wines are generally slightly more approachable than Grandes Places, but this is a big place and there is considerable variation among its sectors, with some areas that point south and some that point east. Clusel Roch is again a big name here, and you also have vines farmed by Rostaing and Gaillard.

Tupin - Go in the other direction from Ampuis – down river, or southwest – and you get to the commune of Tupin, or more fully Tupin-et-Semons. The village itself is actually up on the plateau. Its vines descend to the roadside of the N86.

Here you are approaching Condrieu, and this is apparent from the soils, where you find loose granite and sand. It is also apparent in the vineyards, where you find more Viognier planted among the Syrah vines.

The wines produced are among the lightest and most aromatic of Cote Rotie. In Burgundy terms, you might thing of Tupin as Chambolle Musigny (while Verenay could be Gevrey Chambertin and Ampuis, the village with everything, is clearly Vosne Romanee).

There are no big name vineyards here, though Jean-Michel Stephan makes a beautiful single vineyard Cote Rotie from one site, called simply Coteaux de Tupin. Other important growers down here include Vernay (who's not from Verenay!) and Duclaux.

St Cyr - Lastly we have St. Cyr, at the far north of the AOC, past Verenay. This was not part of the original AOC, designated in 1940, but added on in the 1960s. Like many of the add-ons in the Northern Rhone, it is distinctly inferior. And now we are really close to Lyon, so many folks really did figure that a new gas station was the way to go. Anyway, you are in the schist half of the AOC, but the wines here are not as structured as you might expect, though the schist does come through in the blackness of the fruit.

Top Producers

Domaine Jamet – If I had to pick one producer to provide me with all my Cote Rotie needs, and price were no object, it would be Jamet. The wines have a purity and elegance that rivals everyone else making wine today in the AOC. If Chave were to make Cote Rotie, the wines would taste like this. Note that there was a split recently, and one of the brothers went off to set up his own domaine, Jean-Luc Jamet. Jean-Luc’s wines were perhaps a little mixed at first, but recent releases have been superb. Pricing is still quite a bit lower than the Domaine’s, so for now it represents quite a nice buying opportunity.

Domaine Gilles Barge – Confining myself now to under $100 bottles, Gilles Barge would be my one choice if I only had one. They follow traditional practices that would not have seemed out-of-place in Gentaz’s cellar and have holdings in the top terroirs around Ampuis. The Cote Brune single vineyard bottling is the real stand-out here, though their blend “Cuvee de Plessy” is a fantastic and fairly priced Cote Rotie that you can enjoy without much cellaring.

Rene Rostaing – Rostaing, having inherited vines from both Gentaz and Albert Dervieux Thaize (another traditionalist legend, whose 1983 is the greatest Cote Rotie I’ve ever tasted, ahead of even top vintage Gentaz!), was perhaps destined for greatness. But while his wines have always been good, I was not really convinced that they belonged in Cote Rotie’s top tier until his son Pierre took over a few years ago. Now the wines are sensational. Single vineyards from Cote Blonde and La Landonee are special; the Ampodium is a superb blend designed for early drinking.

Guigal – This is a must-know producer, primarily because they produce about 1/3 of the AOC’s wines through both contracts and their own holdings. They are also hugely important for the historical reasons mentioned above. With their “La La’s” – the three single vineyard wines they release called La Landonne, La Turque and La Mouline – they have produced vintage after vintage of monumental wines that have won top praise in the international press. All that said, they also deserve criticism for a style that is overtly ripe and oaky, and for release prices that are all but prohibitive for wine-lovers of ordinary means.

Domaine Bernard Levet – Levet is another traditionalist who makes some of Cote Rotie’s most soulful wines. For years, they were perhaps a little too soulful for some, often showing funky and bacterial notes. Bernard’s daughter took over a few vintages ago, however, and the wines now seem a little cleaner and purer. The wines remain reasonably priced and while they do not have quite as classical a profile as, say, Barge’s, they are terrific and highly recommended.

Benetiere – I hate to put a name like Benetiere on this kind of list because he is so small production and culty that it’s super hard to find the wines. He combines old-school techniques with Burgundy-like purity and focus. The Cordeloux is a blend from the southern, granitic portion of Cote Rotie, and is a wine that you have a chance of finding. Dolium comes from the Cote Brune, and he makes only a barrel, so it is almost impossible to find.

Clusel-Roch – This producer specializes in the schist soils of Verenay, and makes wines that marry the natural power of the village with a surprising elegant, floral touch. The single vineyard from Grandes Places is the key wine here, and definitely a wine to cellar in all but the disaster vintages.

Xavier Gerard - This is a newish producer that I'm really excited about. He inherited his father's vines in 2012, and then blew everyone's minds at a Decanter blind tasting of the 2015 vintage, besting all the top names of Cote Rotie. The style is down the middle: elegant and polished, with good intensity but no excess. His holdings are in good sites in Ampuis, and his village blend is an excellent go-to source for reasonably priced Cote Rotie. He has a single vineyard bottling from La Landonée that is extremely rare.

I could go on. Unlike Hermitage, Cote Rotie has quite a good number of producers, thanks to a larger total surface area and also because holdings tend to be small. Very little Cote Rotie is actually bad, and whenever you encounter a bottle it is usually worth trying, even if you’ve never heard of the producer or it is from some super market négociant. Some other good names that are particularly fun to stumble across are Burgaud, JM Stephan (especially the natural Cote Rotie from Tupin), Champet and Bonnefond.

Buying, Drinking and Collecting Cote Rotie

If you have room for just a dozen Cote Roties in your cellar per vintage, I would try to get a few bottles of Jamet, maybe a bottle or two of a top wine like Clusel-Roch’s Grandes Places or one of Rostaing’s single vineyards, and then fill out the case with good values form the likes of Barge, Xavier Gerard or Bonnefond. If you have room for a second case, maybe pick a couple of favorites and go deep! I might do four bottles of Levet Chavaroche, four bottles of Barge Cote Brune and then try to find four bottles of Benetieres.

In lighter vintages, you can start drinking the wines designed for earlier drinking – Rostaing’s Ampodium or Barge’s Cuvee de Plessy – right away. From bigger vintages, drink the same wines anywhere from two to ten years out. Top wines need at least ten years as a rule – though some particularly forward vintages will start to show sooner (2011s are really good right now in 2020 for example).

Treat these wines as you would Burgundy! Get to know the different sites and the range of nuances that they produce.

Drink them with steak when they’re young, roasted chicken at middle age, and elegant truffled meals when fully mature. These are wines to fall in love with.

SHOP COTE ROTIE IN NEW YORK.

SHOP COTE ROTIE IN SAN FRANCISCO.

Jeff Patten is one of the founders of Flatiron Wines. He has been buying and selling wine, and exploring wine country, for over 20 years, and drinking and collecting it for far longer. He is WSET certified (level 2).