Marvels on the Margins: Part 2 - Vino Nobile di Montepulciano

This is Part 2 of a series called "Marvels on the Margins" which explores the over-looked regions of Italy. You can read an introduction to the series here, as well as Part 3 Trentino-Alto Adige, Part 4 Aglianico, Part 5 Guide to the White Wines of Fruili and Part 6 The Guide to Mt. Etna

When I first discovered Italian wine – it was a family trip to Tuscany in 1992 – I didn’t at first imagine that Vino Nobile di Montepulciano would ever be considered a “Margin”. My mother had booked us – by mail! – a beautiful country house (basically a villa, but before Tuscan villas were dressed up with swimming pools and viking ranges) in the village of Montefollonico.

One day, we hiked to Montepulciano, to the east, by descending from Montefollonico’s hilltop, crossing a few miles of valley-floor vineyards, and then re-ascending in Montepulciano. It was a brutally hot summer day, we didn’t bring enough water with us, and when we finally arrived and could re-hydrate Montepulciano seemed like the best place I had ever been. It wasn’t just the water: it was a charming Tuscan town, already pretty touristy, with a main street that wound to the top of the village, passing many charming wine boutiques and restaurants.

We could also go to Montalcino from our villa, but this was a car ride of about 30 minutes (thanks to roads that wound around historic vineyards; as the crow’s fly, it would have been more like 10). This was a village that was already very much an international tourist destination. In the early 1990s, Brunello di Montalcino had been fully discovered, maybe even more so than Barolo.

Barely of drinking age, I quickly learned that Montalcino’s wines were pretty expensive, and that a good second choice, far more affordable, was Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. It was a good lesson, and we happily consumed many bottles. I had discovered my first Marvel from the Margins.

Now, though, looking back, I realize that I didn’t quite understand what I was getting from Montepulciano – or of Marvels in general. In my wine-uneducated mind, I saw Vino Nobile as a “poor man’s” Brunello. Years later, when I entered the wine industry, I continued to see it that way. And in general that is how the whole wine industry here in America treated it, and continues to treat it.

I’ve since discovered the truth: that Nobile (as many people in the wine world call it for short) is, in its own right, a singular and great expression of Tuscan Sangiovese. It may be cheaper than Brunello, but that’s just a bonus, and not its raison d’etre. Montepulciano has its own terroir, its own stories, its own traditions, and its own personality

The point of this blog post is to explain all of that to you.

But first thing’s first: What is the difference between Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and Montepulciano d’Abruzzo?

Yes, let’s get this confusion out of the way. In the region of Tuscany, Montepulciano is a village. Vino Nobile di Montepulciano is the “noble wine” of the village of Montepulciano. It is made primarily with Sangiovese. In the region of Abruzzo, Montepulciano refers not to a village but to a grape variety that produces spicy red wines.

A Brief History of Vino Nobile

Wine history can be pretty boring, but there are definitely a few things worth knowing about Nobile’s past. Here is the most important: Vino Nobile used to be considered really really good. Poet Francesco Redi called it the “king of all wines” in the 1600s. Good old Thomas Jefferson called it “a very favorite wine” and “a necessary of life” (sic.). Voltaire praises the wine in Candide. There’s a reason that this wine got the nickname “noble”!

And we could go back a lot further than that. The village of Montepulciano still has old tunnels constructed by the Etruscans, who were likely the first to produce wine in the area. Legend has it that when the Gauls sacked Rome (in 390 BC), it was the wines of Montepulciano that these beer drinkers were really after.

Vino Nobile’s exalted status lasted well into the 20th century. In fact, as recently as 1980, it was the first wine to be awarded “DOCG” status when the concept – meant to signify that an Italian DOC is extra special – was invented, alongside just Brunello and Barolo.

You’d think that Vino Nobile would be at the top of Italy’s wine hierarchy today! And maybe one day it will be again. But something happened after 1980, and the wine went into relative decline. Even today, it can fetch as little as just one third the price of a comparable Brunello di Montalcino.

So what went wrong? Matt Kramer theorizes in his excellent book on Italian wine that they simply got lazy and rested on the laurels of their glorious past. My own theory is that what happened to Nobile is the rise of Brunello.

Nobile’s Dark Times

In 1982, after years of cold and stern vintages, Bordeaux had a year of warmth and opulence. The British media was not impressed. The American Robert Parker, still mostly unknown, pronounced the vintage to be great.

It’s no exaggeration to say that in this single moment wine journalism would have a greater impact on the world of wine than at any other in the last 50 years. Cool and austere was no longer hip. We entered into the world of opulence.

When it comes to Sangiovese, one wine stands above all else when it comes to opulence: Brunello di Montalcino. While at their best, Brunello is capable of great elegance, it is unquestionably at the opulent end of the Sangiovese spectrum. Opulence is what the world of wine wanted, and Montalcino – already the more famous of the two wines, for sure – started to pull ahead even further. When I visited both towns in 1992 – just a dozen years after Montepulciano seemed equal to Montalcino in winning DOCG status – the gap in price and prestige had become enormous..

Then Montepulciano made an unforced error. Producers took a look at the marketplace and they decided that they wanted to be opulent too. They didn’t have the same raw material as their colleagues in Montalcino, but they had a couple of other tools at their disposal. Like anywhere, they could age their wines in French oak barrels. And unlike in Brunello, which was legally mandated to be 100% Sangiovese, Vino Nobile’s Sangiovese could be blended with up to 30% other grapes – including Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc.

So in an effort to recapture market share, Nobile producers went international in style. By the time I made my appearance in the wine trade (2005) and started to taste Vino Nobile as a professional, I was not at all impressed. Almost everything tasted like a generic, international red wine loaded with wood flavors. And it just didn’t work with consumers. They had just seen too many wines like this before. Nobile continued to lag far behind Brunello in terms of pricing and prestige, and soon enough it took up even less space on wine store shelves and restaurant lists.

Vino Nobile’s Renaissance

I finally returned to the village of Montepulciano in 2018. I was invited there for a burger – this was the era when fancy burgers were becoming so ubiquitous throughout Italy that you could even find them in small hilltop medieval villages.

The burger was pretty good. But the Nobile that the proprietor selected for us was a revelation. It had all the depth and sophistication of great Brunello. It was thoroughly Tuscan in character, with no international sheen provided by French oak. It didn’t taste quite like Brunello. Nor did it taste like Chianti. It was a different expression of Chianti. Seamless and elegant, and wonderful.

It turns out that this was the early sign of a Vino Nobile renaissance. Producers were dialing back the oak, taking terroir seriously, and upgrading facilities. After that trip I started to taste Nobile more regularly. Still hit and miss at first, the wines seemed to get better and better every vintage.

Today, the price of Brunello is still 2-3 times as high as Vino Nobile di Montepulciano. But the gap in quality is just no longer there – or at least not anywhere close to that ratio. The market just hasn’t caught up yet.

Today, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano offers some of the most compelling values from anywhere.

What are the Grape Varieties of Vino Nobile

Like in Chianti and Brunello, Vino Nobile is a Sangiovese-based wine. Like in Chianti – but unlike in Brunello – the Sangiovese may be blended with other grapes, although at least 70% of the wine must be Sangiovese. The rest can be made up of any indigenous Tuscan red variety (such as Canaiolo or Colorino), or a French grape such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot or Cabernet Franc. Tuscan white grape varieties are also permitted, but can make up no more than 5% of the blend.

What’s with this blending? It’s because Sangiovese is a difficult grape to ripen. It has no problem doing so in warmer Montalcino, and therefore no blending there is required. In Chianti, Sangiovese has (at least historically) had a rough time developing full ripeness. Blending with early-ripening grapes was the solution. Montepulciano followed suit, and the local laws permit blending. It’s the same principle as you find in Bordeaux, where Cabernet is traditionally blended with the early-ripening Merlot.

In the first couple of decades of the DOCG’s existence, French grapes were used fairly widely, contributing to the international, more opulent style that I criticize above. These days, French grapes are rarely used, and many use 100% Sangiovese. Furthermore, starting in 2021, to be designated “Pieve” – more on this below – a Nobile must contain at least 90% Sangiovese and no foreign varieties.

So perhaps the most important thing to know about Vino Nobile’s grape varieties isn’t the blending, but rather the kind of Sangiovese. It’s called Prugnolo Gentile, which means “gentle plum”. This is said to be a reference to its appearance, but I do find the Vino Nobile fruit to have a slightly plummier fruit profile than other Sangiovese. But treat this information with care, as many Prugnolo Gentile vines have been replaced over time with standard Sangiovese vines – although, in good news, this appears to be a trend that is reversing as the renaissance in Vino Nobile proceeds..

What are the Aging Requirements of Vino Nobile?

Vino Nobile needs to be aged for two years before release, of which at least one year must be in wooden cask. That means that here in the US, as of the time of writing in February 2024, we have mostly 2020s in the marketplace, as those wines would have been finished towards the end of 2020 or the beginning of 2021, needed to be aged for two years, and then bottled, picked up and shipped to America. 2021s should start to appear soon.

An additional year of aging is required to label a wine “Riserva”.

What are the wines of Vino Nobile like?

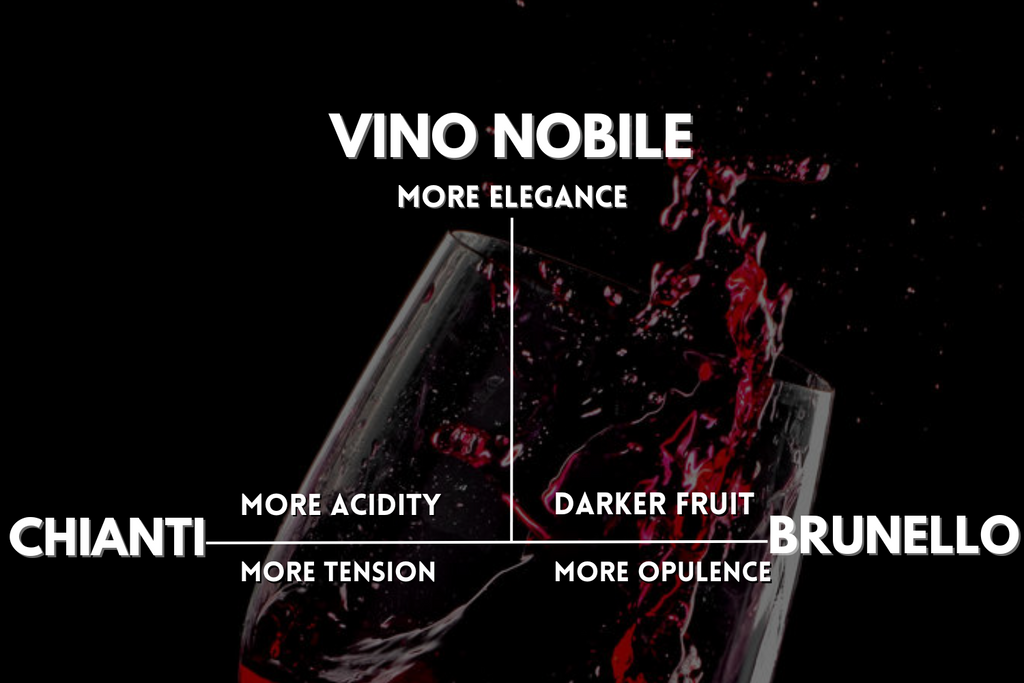

This may be the most important question about any wine, and I am only getting to it now because some much of the information above is background that explains what I am about to say. The very simplest way to explain Vino Nobile di Montepulciano is that it is something like halfway between Chianti and Brunello. This is not entirely true, but close enough that it serves as a useful rule of thumb – the kind you can take with you to the Italian restaurant next time someone hands you the wine list. But there is a lot of nuance here and it’s worth going into the details.

Sometimes, being halfway can be a poor compromise. But in this case, being halfway is the best of both worlds. I think of it in terms of Barolo communes. La Morra provides elegance and aromatics. La Serra structure and power. It’s the villages in between, Castiglione and the Commune of Barolo, that offer both, producing, in top sites like Cannubi or La Rocche, what may be the most complete Barolos of all.

In the world of Sangiovese, Chianti offers tension. Acidity is high, and tannins are often slightly underripe. Brunello offers opulent fruit and fully ripe tannins. It is in Montepulciano that Sangiovese manages to combine both: gushing fruit, balanced out by Chianti-like edginess. For me, it is ideal.

Antonio Galloni makes a similar point but puts it slightly differently, writing, back in 2021, that Vino Nobile “has more structure and depth than Chianti Classico, but less opulence than Brunello. That’s a pretty appealing mix in my book.” Indeed it is!

Another way that some commentators have thought about it is in terms of phenolic ripeness. As many readers will know, grapes become ripe in two different ways. They become sugar ripe as their sugar develops and acidity levels fall. They become phenolically ripe as their physical components – the pips, the stems, the skins – develop, losing their green, bitter notes. Ideally, both kinds of ripeness are achieved at the same time. Arguably, Brunello’s problem is that the grapes are already too sugar ripe by the time they are phenolically ripe, resulting in lower acidity and excessive opulence. In Chianti, this can happen too. Most sites are actually warmer than in Montepulciano, with temperatures in Radda’s summer typically reaching 30 degrees celsius, and Montepulciano only at 28. This is one of the reasons that it is not 100% accurate to think of Montepulciano as being halfway between Brunello and Chianti. Significantly, it means that in Montepulciano Sangiovese can take a long time to develop sugar ripeness – harvests in October are common – ensuring that there is plenty of time to also achieve phenolic ripeness.

So what does Vino Nobile taste like? At their best, Vino Nobile produces very fine and elegant Sangiovese. Thanks to that great balance between structure and fruit ripeness, the wine has a seamlessness to it that brings to mind the over-used wine descriptor “smooth”. The fruit shows plenty of Sangiovese’s signature cherries, though they are perhaps not as wild as Brunello’s, or as bright red as Chianti’s can be (as in the village of Radda). As mentioned above, the fruit quality can also be a little plummy. The herbaceous side of Sangiovese is present, but it can come off as more floral, like rosewater or violets, and sometimes veers towards a more exotic spice. Mineral notes include iron ore, leather and the same earthiness that you sometimes find in Brunello.

But here I’m generalizing liberally. Chianti and Brunello are big places with lots of diversity. North facing sites in Brunello, or Chiantis from a village like Gaiole – known for wines of greater depth – might come across as Vino Nobiles. And in the course of “researching” this guide, I certainly drank bottles that might be confused, blind, with a Chianti or a Brunello.

And Vino Nobile di Montepulciano is itself a diverse place, with a range of producers, styles and terroirs. Let’s dive into that now…

The Terroir of Vino Nobile di Montepulciano

Leave Montalcino and head eastward, and you descend into the Val d’Orcia. This valley is the source of many Tuscan dreams: imagine rolling hills, perched medieval villages, olive groves and cypress trees. Plus plenty of vines. Continue on for about 20 miles and you will start to ascend one particularly high hilltop town. That is Montepulciano.

Given their proximity, you will not be surprised to learn that the geology and soil type of Montepulciano and Montalcino are fairly similar, with both DOCs being dominated by sand-clay soils. But it’s the differences that are more interesting. Montepulciano’s soils tend to be sandier, and there is also more red soil (from the presence of iron). As noted above, Montepulciano also tends to be cooler, as it is a little higher up into the Apennines, and there is more fog, protecting the grapes from sunshine. A nearby lake also offers a moderating effect. These features, together, are also why Montepulciano is actually cooler than, not just Brunello, but also most of Chianti Classico. This is an area that rarely sees a day above 83 degrees fahrenheit. It perhaps has a bit less to fear from global warming than Montalcino.

Geologically speaking, Montepulciano, like most of Italy, was completely under the sea until a couple million years ago. It is dominated by soils from the Pliocene era (which also covers large parts of Montalcino). These are typically thin clay-sand soils that produce structured and powerful Sangiovese. A good chunk of Montepulciano’s soils, however, are from the Pleistocene era. These are deeper, alluvial soils that produce lighter, more fragrant Sangiovese. Could this combination of soils be one of the keys to Montepulciano’s balance between Brunello-like power and Chianti-like aromatics? Again, the situation seems a bit like Barolo, where lighter, more fragrant wines from sandier soils are sometimes blended with massively structured wines from limestone soils.

At Boscarelli, one of my favorite producers, they have done experiments dividing their soils into three types and producing three different wines. They found that sandy soils produced more aromatic wines, clay soils more power, and red soils more depth and acidity. There is plenty of all three in Montepulciano, and they blend together quite nicely.

Pieve

We’re soon all going to learn a lot more about Montepulciano terroir and how different soils types impact the wine. That’s because, starting with the 2021 vintage, Vino Nobile is rolling out the system of Pieves.

A Pieve is the local word for a parish, and Montepulciano has 12 of them. Starting with the 2021 vintage, a Vino Nobile may bear the name of its Pieve if its grapes come entirely from that Pieve, it has at least 90% Sangiovese, it has no foreign varieties, and it meets the aging requirements for a Riserva (three years). The first Pieves, from the 2021 vintage, will come on to the marketplace in 2025.

Aside from a fear that this will offer Vino Nobile producers a chance to increase their prices, I’m pretty excited about this development. I won’t go through all the Pieves here, but from multiple accounts each Pieve does seem to reflect a unique terroir profile. So Valiano, for example, will show us what wine tastes like when the soils are Pleistocene, Sant’Albino will show us red soils, Caggiole sandy soils, and so on. We are going to learn a lot about Sangiovese terroir!

Buying, Collecting and Drinking Vino Nobile

As you can tell from this guide, I”m a big fan of Vino Nobile and if there is one general buying recommendation I can give you it is this: invest a little less in Chianti and Brunello, and make room for Vino Nobile. But of course, it’s the details that matter.

Producers

As little as ten years ago, this would have been a very short section of this guide. Virtually everything I tasted was too oaky and too international, probably because of Cabernet or Merlot. I did drink the wines a bit, but tended to stick to a couple of favorites that consistently showed real Vino Nobile personality, like Le Berne and Villa Sant’Anna.

I continue to enjoy those two producers, but now there are so many others to choose from. Avignonesi was purchased in 2008 and went 100% biodynamic and 100% Sangiovese. Their straight Vino Nobile is quite a bargain, usually selling in the low $20s. It’s a great place to start exploring the DOC.

If I had to choose one signature producer of Vino Nobile, it would be Boscarelli, whose wines really manage to find that balance between opulence and elegance that the DOC is capable of. They produce a very classic Vino Nobile – about 80% Sangiovese and the rest native Tuscsan varieties. Their “Nocio” Vino Nobile is 100% Sangiovese from a single Cru and is consistently one of the best wines in the DOCG.

Dei may be my personal favorite producer at the moment. Their vines are fairly high on slopes just below the village of Montepulciano itself, where the clay soils produce wines that are at the deeper and more structured end of the DOC’s spectrum. Wine are aged only in giant wood casks and in bottle.

Poliziano is an example of a producer, like Avignonesi, that has been transforming itself from an internationalist into a winery that produces wines that are more distinctively Vino Noile. Thus, there is more emphasis today on Sangiovese and less on barriques than there used to be. The wines still have a nice polish, and I find them quite attractive.

Salcheto is another fully biodynamic producer that uses 100% Sanvgiovese in its Nobile. There are mostly large casks here, though a few small barrels. The emphasis here is definitely on herbs and minerals and this certainly is not a wine that is dressed up with international sheen.

There are plenty of other producers – around 80-90 – and many of them are good. There are still a few duds around, for sure, but generally I have decent luck simply opening up random bottles that I find, such has the quality in the DOC improved in recent years.

Collecting and Drinking

If you’re experienced with other Sangiovese wines – mainly Chianti and Brunello – you know that these are wines that can age. In my experience, Vino Nobile behaves a little more like Chianti than Brunello in this regard. That is to say that the wines tend to be delicious on release, but also have no problem aging and developing for five to ten years.

There are a couple of important caveats here. I do come across some Riserva bottlings and single vineyards that are too structured, too closed down, too oaky, or some combination of those three, when first released. These are wines that appear to require some time.

The bigger caveat is this: Vino Nobile’s quality revolution is still quite recent. It simply hasn’t, yet, offered me an opportunity to buy, cellar and drink at 10+ years of age very many examples of high quality Vino Nobile. Everything I say about aging these wines is based primarily on my intuitions tasting the wines and comparing them to similar examples of Brunello and Chianti. But my basic view on these wines – that they are great to drink young, will probably develop nicely over 5-10 years, and who knows beyond that – seems to be a fairly consistent view among the wine professionals I talk with or read.

Vintages

Vintages matter here, like in any wine region, but they matter less here than in nearby Brunello. This is because the single most decisive factor in the success of a vintage these days is heat: in many years, it’s just too warm to make elegant Brunello. This is far less true in Montepulciano, where excessive heat is much less common. Thus, both 2017 and 2018 were difficult vintages in Brunello. They weren’t amazing in Montepulciano, but they were much better. On the flip side, some vintages in Montepulciano show issues with under-ripeness. 2014, for example, was not a success in Montepulciano. And many 2020s taste more like Chiantis than Brunellos, with nervy tannins and acidities.

On the whole, 2019s are excellent. 2021s also appear to be quite promising, and I look forward to starting to see them in the US in the next few months. After 2021, it’s been a pair of warm years….we’lll see how Vino Nobile responded, but I’m more optimistic about Nobile than I am Brunello!

Please head over to Part 3 of this series to read about Trentino-Alto Adige

Jeff Patten is one of the founders of Flatiron Wines. He has been buying and selling wine, and exploring wine country, for over 20 years, and drinking and collecting it for far longer. He is WSET certified (level 2).