Ultimate Guide to the Terroir of Sancerre, Part One

Sancerre is one of France's great wines and this guide will give you all the details on what makes it so good. Sancerre comes in red, white and rose, and all three colors of Sancerre are delicious and fascinating and worth getting to know.

White Sancerre is by far the most famous. A white wine made from Sauvignon Blanc grapes grown in the Sancerre Appellation of France’s Loire Valley, Sancerre Blanc (as it is known in French) is made from Sauvignon Blanc grapes, and has become a favorite around the world as one of the most dependably tasty, crisp, aromatic white wines -- and one that is reasonably priced, too.

Delicious on its own, and great with a variety of foods, it’s no wonder Sancerre is world famous!

Flatiron’s Four-Part Guide to Sancerre

But Sancerre is much more than just a dependable, affordable white wine. The Sancerre region makes many truly great wines of terroir that every wine-lover will be richly rewarded for getting to know, including red wines and rosés made from Pinot Noir.

In this post we’ll give you the basic lay of the land in Sancerre to help you better appreciate your next glass or bottle of the wine. The next three posts will give you all the details you need to really begin to appreciate the finer points of this famous, and yet underrated wine.

Sancerre: a Wine, a Village and an Appellation

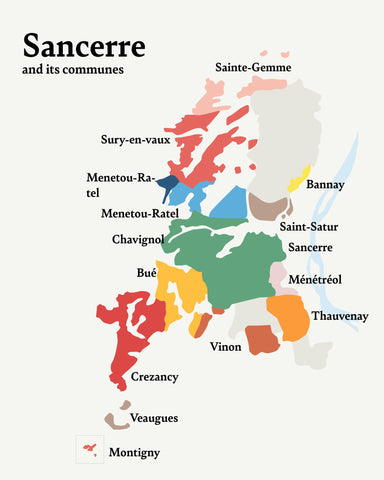

The Sancerre appellation is named after the village of the same name. But the appellation covers vineyards planted in 14 surrounding communities. So, although a Sancerre wine must come from the Sancerre region, it may not come from the village of Sancerre.

Why is Sancerre So Popular?

First and foremost, Sancerre is popular because it tastes great!

Over the last several decades, the name Sancerre has become synonymous with crisp, bone-dry white wine with lovely aromatics and mouth-watering flavors of citrus and other fruits.

What’s more, those white Sancerre are dependably good. Virtually any Sancerre you find in America will be of decent quality, with a lovely freshness and pretty, delineated fruit. “A glass of Sancerre, please” is one of the safest asks you can make in a wine bar or restaurant. As such, it's become one of wine's greatest hits, a wine with nearly unparalleled brand recognition and customer devotion.

Some of Sancerre’s popularity is down to the popularity of its grape, Sauvignon Blanc. Naturally crisp, with citrus overtones, Sauvignon Blanc overtook Chardonnay as the “glass of choice” among many casual wine drinkers years ago. New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc is, of course, an enormous wine phenomenon. And California has its history “Fume Blanc” and other SB stars.

But there’s more to Sancerre than just a popular grape.

Much of Sancerre’s vinous consistency owes to the Sancerre region’s ideal climatic conditions. Centered on the village of Sancerre in the Loire Valley’s Central Vineyards, the region enjoys a continental climate, not unlike Burgundy (Sancerre is actually closer to Burgundy than it is to most of the Loire’s other famous regions). This climate allows grapes to ripen with fully developed, complex flavors, while also preserving the acidity necessary to keep the wines feeling fresh and food friendly.

Sancerre also has the kinds of soils that make truly great wines possible, with a mix of limestones, flints, clays and gravels giving variety and character to the wines. Add in a combination of rolling and steeper hills, varied expositions, and devoted growers and winemakers, and you have a recipe for great wine.

Sancerre’s Surprising History of Red Wine

Sancerre has some of the most enviable white wine terroir in all of France. But the funny thing is that historically the region made much more red wine (from Gamay and Pinot Noir) than white. And in fact, Sauvignon Blanc wasn’t even the main white wine grape in the olden days; even though Sauvignon Blanc had been around for centuries, that honor went to Chasselas (which is now mostly limited to Pouilly-Sur-Loire).

But all that changed in the 19th century when Phylloxera, the American-imported vineyard disease, wiped out all the old vines. Winemakers discovered they could defeat the disease by grafting their choice of French grape onto imported American rootstock (which was resistant to the pest). Faced with a clean slate and the chance to graft whatever they wanted onto the American rootstocks, the locals went by and large with Sauvignon Blanc.

Why did they choose Sauvignon Blanc? There are reports that this was because that variety took to the grafting technique better than most. But there are other reports that even before the widespread replanting, Sauvignon Blanc from the region fetched higher prices than any other grape; wine lovers had long known just how perfect the matching of Sauvignon Blanc and Sancerre’s terroir was.

Whether it was mostly for technical reasons or because the wines proved superior, by the time the train lines connected Sancerre to Paris, the region was established as white wine country and Sancerre Blanc was able to start to become a go-to wine in Paris bistros and shops. From that perch, Sancerre Blanc was able to begin to take its place among the world's favorite white wines.

There is still Pinot Noir planted in Sancerre today. It makes some of France’s greatest rosés -- wines with depth and minerality as well as the joyful fresh fruit we all crave from rosé. It also makes red wines that can be great value Pinot Noir alternatives to Red Burgundy, with a lightness and mineral or herbaceous freshness that balances the Pinot fruit.

Sancerre’s Villages and Soils

The irony of Sancerre’s market supremacy is that, despite all the fame, its incredible terroirs are largely unexamined by casual wine drinkers and devoted geeks alike. Even many casual wine lovers know that white Burgundy varies enormously from sub-region to sub-region or even plato to plot -- Meursault is different from Chablis which is different from Puligny Montrachet.

But the sheer power of the name “Sancerre” has obscured the rewarding subtleties that make a Sancerre from, say, Chavignol different from a Sancerre from Bué.

This same lack of awareness extends beyond terroir; many Sancerre Blanc fans know to ask for Sancerre, but are totally unfamiliar with the names of its best and most historic winemakers—producers who define the possibilities of what Sancerre can be.

But this is slowly changing. Today we’re looking at just some of the fundamental aspects of the region, while our next three posts will look at Sancerre in greater detail. We hope that by the end of this series you’ll agree with us that Sancerre is one of the great wine regions for casual wine drinkers and devoted wine geeks alike.

What Makes Sancerre’s Soils So Special?

Sancerre is a region of unique and exceptional terroir which, from a geological perspective, can be loosely broken into three parts:

(1) silex, is clay with flint, which makes delineated and elegant wines that age well;

(2) Kimmeridgian limestone (aka: terres blanches), is a chalky soil made of ancient oyster fossils can be the most structured and take the longest to express themselves, but are delicious and full of personality;

(3) Oxfordian limestone, which comes in two main varieties, referred to as caillottes (a mix of limestone and gravel) and griottes (a mix of limestone and clay) tends to make the earliest-drinking Sancerre, often charmingly aromatic, floral and nuanced, but sometimes also deceptively deep and long-lived.

Each of these soils seems to have a pretty significant impact on the taste of the wine. Scientists debate how and how much soils actually influence the taste of the wines they make, but if you’re curious about how important soils are to the taste of a wine, Sancerre is a great region to develop your own understanding of the issue.

Learning about Terroir by Drinking Sancerre

Since Sancerre has a fairly homogeneous climate and, like most of Burgundy, uses just one grape for its reds and one for whites, it's a perfect region for discovering the effects of geology on a wine's taste. To get to know Sancerre intimately is to have had a crash course in terroir itself.

Of course, not all Sancerre is so terroir-specific. Erosion over the aeons has mixed two or all three classic soil types in some vineyards, and given others unique characteristics.

What’s more, plenty of great producers bottle wines that blend fruit from two or even all three soil types. Just as many a traditional Barolo producer (think Bartlolo Mascarello) will prefer to produce a wine that blends multiple terroirs rather than making a single commune wine, so to there can be something incredibly satisfying about a sancerre that has some of the finesse and smoky overtones of silex soils, undergirded with some of the kimmeridgian chalkiness.

Is There a Grand Cru Sancerre?

Unlike Burgundy, Sancerre's vineyards are not classified into qualitative categories. There are no grand cru, premier cru, or village rankings here. Of course, there are some particularly famous vineyards and, as in Burgundy, wines made exclusively from such sites can command higher prices. But you will never see a Sancerre labelled Grand or Premier Cru.

Does Sancerre have multiple villages like Burgundy?

There are 14 different communes in Sancerre but (once again, unlike Burgundy) the villages aren’t generally used as the organizing principle for the region’s wines. While you will come across plenty of Sancerres with vineyard names on them, and even many Sancerres named after one of those key soil types (just google “Sancerre Cuvee Silex” and you’ll see what I mean), you will rarely see a bottle of Sancerre labelled with the commune name.

Why this contrast with Burgundy? Well, in Burgundy the villages are famous for their unique terroirs: Meursault is rather distinct from Puligny Montrachet, despite their proximity. But in Sancerre the three defining soil types tend to appear, to one degree or another, in many of the villages.

What’s more, while Burgundy’s most famous sub-regions consist largely of a single east-facing slope, Sancerre’s sites can vary in exposition as well as soil and micro-climate -- even within a single village. This introduces another level of complexity that can be delicious, but that makes it harder to identify a distinct village characteristic.

There are, of course, exceptions. Bué has begun to develop a bit of a unique identity among some American Sancerre fans, especially for wines coming from predominantly Oxfodian soils. And, perhaps confusingly, Sancerre’s most famous sub-region isn't even one of the communes; it's the tiny hamlet of Chavignol, home to the famous vineyards of Monts Damnés and Cul de Beaujeu, and such elite producers as Francois Cotat and Gérard Boulay.

So the rest of the posts in this series will break the region down by the three principal soil types. We will discuss a few village names you may see on labels in America, but exclusively to help understand the soil types that we think are the real secret to getting a handle on Sancerre as a true wine of terroir.

Sancerre and Food: Many Matches Made in Heaven

It’s hard to think of a more perfect white wine for food than Sancerre. The bright fruit and crisp acidity makes Sancerre the ideal wine with everything from pre-dinner snacks to fine fish dishes. And while it’s not as famous with oysters as its kimmeridgian cousins from Chablis and Champagne, Sancerre can be amazing with a seafood tower.

And if you’ve ever had the local goat cheese, Crottin de Chavignol, with a simple salad and glass of Sancerre while sitting in the spring sun and watching a Loire Valley town amble through its leisurely midday… well, you don’t need us to tell you how good life can be.

And what about pairing red or rosé Sancerre? Sancerre Rouge is a natural whenever you need a light red with character and freshness: think Salad Nicoise with lots of fresh herbs. Sancerre Rosé tends to be full of pretty fruit but also complex minerality and as such can be great both as a simple summer sipper and also as a pairing with dishes that sneak up on you with their sophistication, like the haute twist on fried green tomatoes with pistachio pesto, piperade, olive oil -- the wine’s fruit balances the tomato while the high tones cut through the piperade and olive oil.

How do I start learning more about Sancerre?

By drinking some! There’s no better way to learn about a region than to dive in and start drinking the wines. As you read on through our guide, you may decide to take a deep dive into the individual terroirs.

But for starters, we think picking an “entry level” Sancerre from a quality producer is the way to go. Give it time to open the glass, take a moment to note the mix of fruit and floral and mineral notes and you’ll see that, at almost every budget, there’s a Sancerre that, more than just a safe glass of tasty white wine, is an artisanal gem well worth paying attention to.

Shop Sancerre Wines in New York.

Shop Sancerre Wines in San Francisco.

What else is there to learn?

Want to go deeper into the details of Sancerre’s terroir and producers? Well read on:

Part Two: Sancerre's predominantly silex (flint) soils, which extend southward from Saint-Satur to Thauvenay, and that area's most significant producers: Alphonse Mellot, Vacheron, and Henri Bourgeois.

Part Three: The Kimmeridgian marl of Chavignol, which has many significant vineyards and producers, including the ones named earlier.

Part Four: The Oxfordian limestone soils, the best wines of which can be found in the commune of Bué. Here we will look at the wines of Lucien Crochet and others.

Want a list of Sancerre’s 14 communes?

Here you go: Bannay, Bué, Crézancy-en-Sancerre, Menetou-Râtel, Ménétréol-Sous-Sancerre, Montigny, Saint-Satur, Sainte-Gemme, Sancerre, Sury-en-Vaux, Thauvenay, Veaugues, Verdigny, and Vinon.

Special thanks for this blog go to our sponsors: